“Regardless of context or the company you keep, you are the most important person in your own learning. Your organization or team or boss might support or stifle feedback. Either way, they can’t stop you from learning. You don’t have to depend on your annual review or your boss’s willingness to mentor. You can watch, ask questions, and solicit suggestions from coworkers, customers, partners, and friends. You don’t have to wait around for someone to train you to sell more shoes. Observe whoever sells the most and try to figure out what they are doing differently. And ask them to watch you. Whatever they suggest, try it on. Experiment with the advice, and if the shoe fits, wear it. Whatever you do in your organization—whether it’s selling shoes or saving souls—you’re surrounded by people who can learn from.” Douglas Stone and Sheila Heen, Thanks for the Feedback

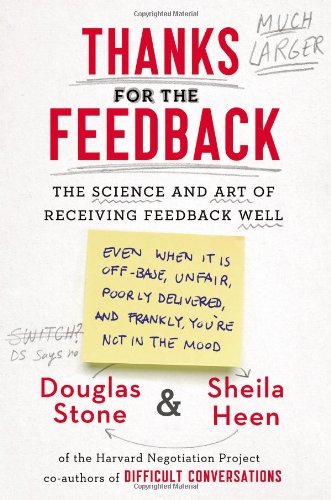

This book has quickly moved to the top of my list of most helpful books that I’ve read. I will definitely be gifting several copies of this book just based on how beneficial it was to me. My heart’s desire as a leader is to always be growing and to be intentional about modeling a growth mindset. Feedback is something that I receive a lot of in my role as a high school principal. Reading this book has given me a much better understanding of how to filter both positive and negative feedback into learning modules that can help me grow as a leader as I desire to serve our school and our families with excellence. The main way this book is helping me right now is by giving me some tools to shape the way that I initially respond to feedback. My identity is in Christ, not in the feedback or the giver of the feedback. My response to feedback should clearly convey my desire to grow while gaining an understanding of the goal of the feedback.

My pastor recommended this book and I’m so grateful that he did! The Christian community is know for having lots of opinions. The goal of this book is to distill those opinions and feedback into profitable information that works for the good of all involved.

I highlighted several things while reading and have posted those notes below…

- We swim in an ocean of feedback.

- Creating pull is about mastering the skills required to drive our own learning; it’s about how to recognize and manage our resistance, how to engage in feedback conversations with confidence and curiosity, and even when the feedback seems wrong, how to find insight that might help us grow.

- Insulation leads to isolation.

- Understanding our triggers and sorting out what set them off are the keys to managing our reactions and engaging in feedback conversations with skill.

- Identity is the story we tell ourselves about who we are and what the future holds for us, and when critical feedback is incoming, that story is under attack.

- Inside a growth identity, feedback is valuable information about where one stands now and what to work on next. It is welcome input rather than upsetting verdict.

- We need evaluation to know where we stand, to set expectations, to feel reassured or secure. We need coaching to accelerate learning, to focus our time and energy where it really matters, and to keep our relationships healthy and functioning. And we need appreciation if all the sweat and tears we put into our jobs and our relationships are going to feel worthwhile.

- The giver has only partial control over how the balance between coaching and evaluation is received.

- What is my purpose in giving/receiving this feedback? Is it the right purpose from my point of view? Is it the right purpose from the other person’s point of view?

- We can’t focus on how to improve until we know where we stand.

- “I don’t say yes or no to a request in the moment. Instead, I ask some sorting questions.”

- To understand your feedback, discuss where it is: Coming from-their data and interpretations AND Going to-advice, consequences, expectations.

- “What do you see me doing, or failing to do, that is getting in my own way?”

- Relationship triggers create switchback conversation, where we have two topics on the table and talk past each other. Spot the two topics and give each its own track.

- A systems view helps us understand what’s producing the frustration or difficulties or mistakes (and hence prompting the feedback) in the first place. It helps us identify root causes and the ways everyone in the system is contributing to the problem. And it explains the contradictory reactions we have as givers and receivers.

- Accidental adversaries are created by two things: role confusion and role clarity.

- Systems thinking corrects for the skew of any single perspective.

- If you soak up all the responsibility, you let others off the hook. Responsibility for learning and fixing the problem is hoarded and the best solutions less likely to emerge.

- Exploring systems skillfully starts with the awareness that what you’re facing may indeed be a systems problem.

- Looking at systems: reduces judgement, enhances accountability, and uncovers root causes

- Our emotions have so profound an influence on how we interpret what happens and the stories we tell about it that, in the wake of upsetting feedback, our upset self distorts what we think the feedback means.

- How you feel in that moment has a big impact on the story you tell yourself.

- The strong feelings triggered by feedback can cause us to distort our thinking about the past, the present, and the future. Learning to regain outbalance so that we can accurately assess the feedback is first a matter of rewinding our thoughts and straightening them out. Once we’ve gotten the feedback in realistic perspective, we have a real shot at learning from it.

- Regardless of whether your reactions are productive or debilitating, it’s enormously helpful to be aware of your particular patterns, It’s especially important to figure out how you tend to respond during that first stage, so that you can recognize your usual reaction and name it to yourself in the moment. If you name it, you have some power over it.

- As you get better at slowing things down and noticing what’s going on in your mind and body, you can begin to sort through your reactions. You’ll get better at distinguishing your emotions from the story you tell about the feedback, and distinguishing both of these from what the feedback giver actually said.

- When you notice the feedback has stampeded over whatever barriers should keep it in place, you have to round up the feedback, and drop it back into the area where it belongs.

- When in the grip of upsetting feedback, we often fail to distinguish between consequences that will happen and consequences that might happen.

- Try looking back on your life from the vantage point of ten or twenty or forty years from now. Ask yourself how significant today’s events are likely to seem in the grand scheme of things.

- So don’t dismiss other’s views of you, but don’t accept them wholesale either. Their views are input, not imprint.

- When feedback contradicts or challenges our identity, our story about who we are can unravel.

- A growth identity is not about whether you get terrific or troubling feedback. It’s about how you hold whatever you get.

- We snatch defensiveness from the jaws of learning.

- “Can we take a minute to step back so that I’m clean on our purposes? I want to be sure I’m on the same page as you.”

- “I want to hear your perspective on this, and then I’ll share my view, and we can figure out where and why our views are different.”

- When you’re at an impasse—when what a giver suggests is difficult for you or even unacceptable—ask about the underlying interests behind the suggestion.

- Feedback conversations are rarely one-shot deals. They are usually a series of conversations over time, and as such, signposting where you stand, what you’ve accomplished, and what you’ll try next helps you travel the road together.

- “Try it on.” “Sit with the possibility for a few days.”

- It’s not all-and-always. Just some-and-sometimes.

- Our subordinates are such a valuable source of information that it’s astonishing that we don’t tap their knowledge more regularly. It’s like crawling along in a traffic jam and ignoring the fact that you have a direct line to the traffic helicopter above—which can see the bigger picture that you can’t from where you sit. They could give you the lowdown on the hot spots, pileups, and shortcuts that would get you the farthest fastest.

- Feedback isn’t just about the quality of the advice or the accuracy of the assessments. It’s about the quality of the relationship, your willingness to show that you don’t have it all figured out, and to bring your whole self—flaws, uncertainties, and all—into the relationship.

- When handling complaints or concerns about the system, make sure to listen and acknowledge. Ask for specific suggestions that might improve the system.

- The point here is not that you have to have an “appreciation system” in place; rather, it’s about having a cultural norm of appreciation that encourages everyone to notice (1) the genuine and unique positives in the work of others, and (2) how each team member hears appreciation and encouragement so that it can be best expressed to that person as an individual.

- If you had to pick between preaching the benefits of being a learner and modeling good learning, well, there’s no contest. In many ways, the manager is the culture: if they’re good learners, they set the tone for a learning culture.

- Regardless of context or the company you keep, you are the most important person in your own learning. Your organization or team or boss might support or stifle feedback. Either way, they can’t stop you from learning. You don’t have to depend on your annual review or your boss’s willingness to mentor. You can watch, ask questions, and solicit suggestions from coworkers, customers, partners, and friends. You don’t have to wait around for someone to train you to sell more shoes. Observe whoever sells the most and try to figure out what they are doing differently. And ask them to watch you. Whatever they suggest, try it on. Experiment with the advice, and if the shoe fits, wear it. Whatever you do in your organization—whether it’s selling shoes or saving souls—you’re surrounded by people who can learn from.